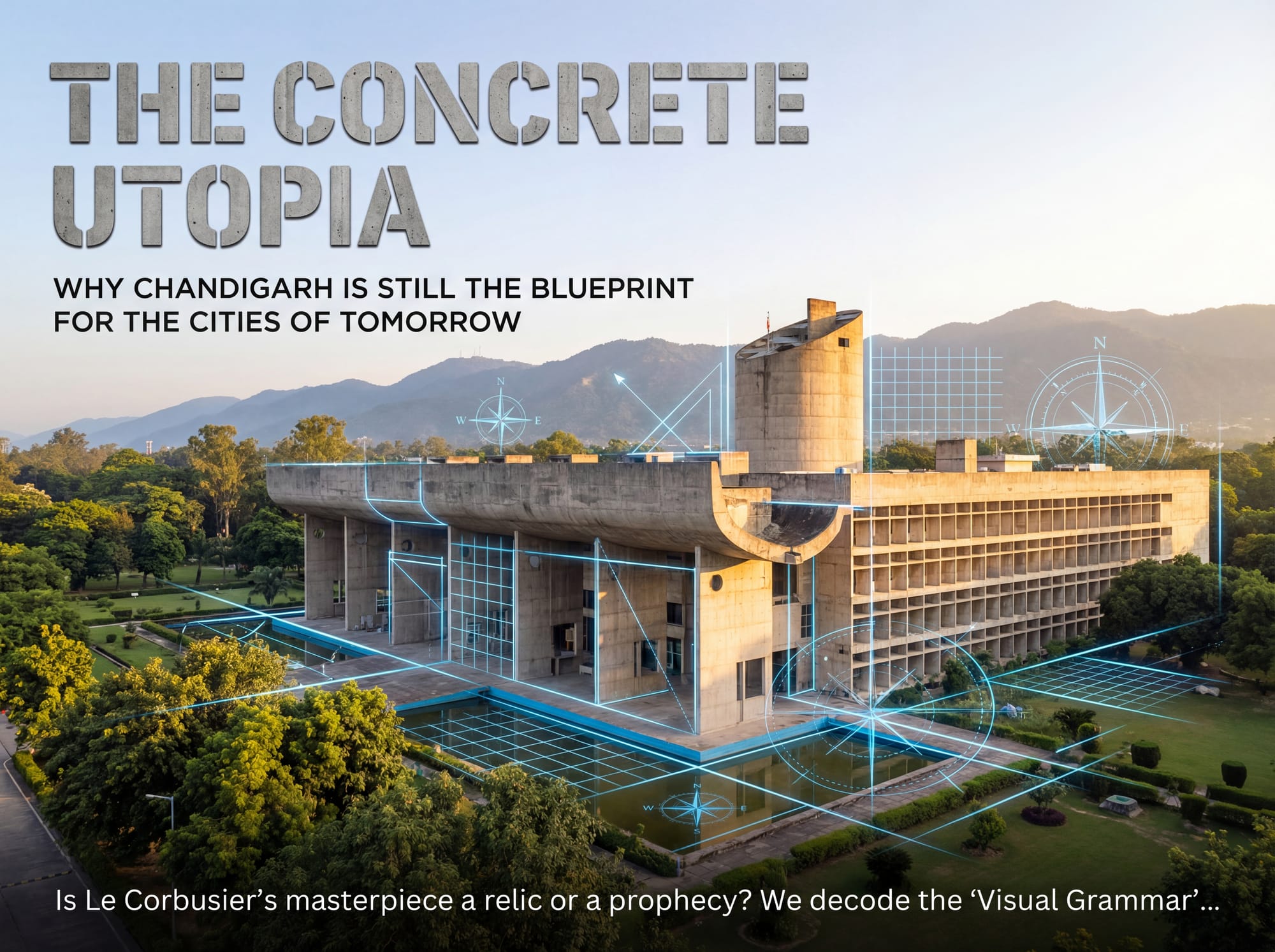

The Concrete Utopia: Why Chandigarh Is Still The Blueprint For The Cities of Tomorrow

Is the most important city in modern architectural history a failure, a relic, or a prophecy? The answer might save our future metropolises.

In the chaos of post-Partition India, a dream was born. It wasn't built from marble or gold, but from raw, honest concrete. Chandigarh, the city designed by the legendary Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier, stands today as one of the most audacious experiments in urban planning the world has ever seen. For decades, critics have called it "un-Indian," "sterile," and "rigid." Yet, as our modern cities choke on congestion, pollution, and chaos, the "City Beautiful" looks less like a mid-century artifact and more like a survival guide.

Chandigarh is not just a city; it is a manifesto written in reinforced concrete. It is a visual grammar of order, light, and space. And for the architects of the 21st century, it offers a critical inheritance: a toolkit for designing livable, efficient, and environmentally conscious cities.

This is the story of that grammar—and how we can steal it to save ourselves.

Part 1: The Genesis of a New Grammar

The Blank Slate of 1952

When India lost Lahore to Pakistan in 1947, the state of Punjab needed a new capital. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru didn't just want a replacement; he wanted a symbol of a modern, secular, and progressive India, "unfettered by the traditions of the past." Enter Le Corbusier.

He didn't bring a style; he brought a philosophy. He treated the city not as a collection of houses, but as a living organism. His master plan was an analogy of the human body:

- The Head: The Capitol Complex (Governance)

- The Heart: The City Centre (Sector 17, Commerce)

- The Lungs: The Leisure Valley (Green belts)

- The Circulatory System: The 7Vs (The hierarchy of roads)

This biological metaphor was revolutionary. It shifted the focus from monuments* to *systems. The "Visual Grammar" of Chandigarh is built on this functional segregation, and it is here that we find our first lesson.

The Tyranny (and Triumph) of the Grid

Chandigarh is famous—and infamous—for its Sector Grid. Each sector is a self-contained neighborhood unit, approximately 800m by 1200m. Inside, it's a microcosm of a city: schools, shops, and health centers are all within a 10-minute walk.

Why it matters today: In the era of the "15-minute city," Chandigarh was 70 years ahead of the curve. The sectors were designed to be introverted, protecting residents from fast-moving traffic. The logic was simple: Speed belongs on the arterial roads; life belongs in the sectors.

"The city must be a place where a child can walk to school without fear of being run over." — Le Corbusier

While critics argue the grid is monotonous, the functional success is undeniable. Traffic flows. Services are distributed equitably. The visual grammar here is predictability as a public service.

Part 2: The Elements of Style - Inheriting the Toolkit

If we strip away the 1950s brutalist aesthetic, the underlying principles of Chandigarh are shockingly modern. Here is the "Visual Grammar" that contemporary architects must inherit.

1. The Hierarchy of Movement (The 7Vs)

Le Corbusier detested the "corridor street" of Europe, where pedestrians and cars fought for space. His solution was the 7Vs (Les Sept Voies), a hierarchy of seven types of roads:

- V1: Fast roads connecting cities

- V2: Arterial avenues

- V3: Fast vehicular roads defining sectors

- V4: Shopping streets within sectors

- V5: Distribution roads

- V6: Access roads to houses

- V7: Pedestrian paths

The Lesson: You cannot design a sustainable city without curating the flow of movement. Today's urban chaos comes from mixing these functions. By separating the V3 (speed) from the V7 (stroll), Chandigarh prioritized the pedestrian experience inside the living zones long before it was trendy.

2. The Green Lungs: Leisure Valley

One of the most radical moves was the Leisure Valley, a continuous green belt that runs through the entire city. It is not a park; it is an artery of nature.

The Lesson:* Green space cannot be leftover space. In Chandigarh, the green belts were planned *before* the buildings. They act as the city's lungs, lowering the heat island effect and providing a social commons. For modern architects, this is the template for *Biophilic Urbanism—designing nature as infrastructure, not decoration.

3. The Architecture of Shade: Brise-Soleil

The "Brise-Soleil" (sun-breaker) is the visual signature of Chandigarh. Faced with the harsh Indian sun and a lack of air conditioning, Corbusier used deep concrete fins to block the summer sun while allowing the winter sun to enter.

The Lesson:* This is **Passive Sustainability. Today, we wrap glass towers in energy-guzzling HVAC systems. Chandigarh teaches us that the building's skin should be a climate-control device. The aesthetic *is the function. Inheriting this grammar means returning to climate-responsive design—using geometry, not electricity, to keep us cool.

---

Part 3: The Capitol Complex - Democracy in Concrete

The Capitol Complex is the crown jewel. It is a UNESCO World Heritage site and arguably the finest ensemble of modernist buildings on earth. It consists of the High Court, the Secretariat, and the Legislative Assembly.

The Open Hand

The symbol of the city is the Open Hand Monument, a 26-meter-high metal structure that rotates with the wind. It symbolizes peace and reconciliation: "Open to give, open to receive."

In a world of walled gardens and gated communities, the visual grammar of the Open Hand is a powerful reminder of the civic duty of architecture. It asks: Does your building give back to the city, or does it just take?

---

Part 4: The Critique - Where the Grid Failed

We cannot inherit the grammar without acknowledging the glitches in the code. Chandigarh is not perfect.

1. The Scale Issue: The Capitol Complex is vast, monumental, and... empty. It was designed for the car and the camera, not the pedestrian. The distances are punishingly long for a walker in the summer heat. 2. Rigidity: The strict zoning laws (separation of residential and commercial) have created a city that sleeps at night. Unlike the chaotic, mixed-use vibrancy of Old Delhi or Mumbai, Chandigarh's sectors can feel sterile after dark. 3. The Class Divide: While designed to be egalitarian, the city's layout inevitably reinforced class hierarchies, with larger plots for officials and smaller ones for clerks, physically encoding the bureaucracy into the map.

The Adaptation: To inherit Chandigarh, we must hack the grid. We need the order of the sectors but the flexibility of the bazaar. We need the zoning, but with mixed-use edges.

"The grid is a tool, not a trap. We must learn to color outside the lines."

---

Part 5: The Future - Adaptive Reuse and Vertical Gardens

How do we apply Le Corbusier's 1950s logic to 2026?

1. From Horizontal to Vertical

Chandigarh is a low-rise city. As land becomes scarce, we cannot afford this luxury. The challenge is to take the quality* of the sector—the light, the air, the community—and stack it. Vertical Gardens** and *Sky-bridges can recreate the V7 pedestrian paths in the sky.

2. Adaptive Reuse

The raw concrete buildings of Chandigarh are aging. Instead of demolishing them, we must adapt them. The visual grammar of "Beton Brut" (raw concrete) is the perfect canvas for green roofs* and *solar skins. Imagine the Secretariat building, covered in a living wall of indigenous plants, cooling the structure and cleaning the air.

3. Responsive Design

The grid of the future must be flexible. "Tactical Urbanism" allows us to change the function of a street for a weekend market or a festival. Chandigarh's wide V2 avenues are perfect candidates for dedicated bus rapid transit (BRT) and cycling superhighways, reclaiming the road for the people.

---

Conclusion: The City As A Living Legacy

Chandigarh is more than a city; it is a question posed in concrete: Can design improve the human condition?

Le Corbusier believed it could. His visual grammar—functional, honest, green, and ordered—was an optimistic bet on the future. Today, as we face the climate crisis and urban overcrowding, that bet is more relevant than ever.

We don't need to copy his style. We don't need more brutalist government buildings. But we desperately need his principles:

- That a city needs lungs (Green Belts).

- That a street is a hierarchy, not a free-for-all (The 7Vs).

- That a building must breathe (Brise-Soleil).

- That the ultimate client is the citizen (The Open Hand).

Chandigarh is an unfinished poem. It is up to us to write the next stanza.

---

Sources & Further Reading

1. Le Corbusier. (1954). The Radiant City: Elements of a Doctrine of Urbanism to be Applied to the Human Habitat. A foundational text on the theory behind the grid. 2. Government of Punjab. (1952). Chandigarh Master Plan. The original blueprint documents. 3. Chandra, Anuradha. (2013). "Chandigarh: A City of Modernity and Tradition." Journal of Architecture and Urbanism. A deep dive into the cultural conflict of the design. 4. Rao, S. S. S. (2015). "Le Corbusier's Chandigarh: A Critical Analysis." Journal of Architecture and Planning Research. Critical perspectives on the functional failures. 5. Singh, S. K. (2017). "Chandigarh: A Case Study of Modernist Urban Planning." Journal of Urban Planning and Development. A review of the infrastructural legacy.